"To lose your mother was to be denied your kin, country, and identity. To lose your mother was to forget your past."

-Dr. Saidiya Hartman

I am the spitting image of my mother.

Three years ago I learned the 'truth' about my origin story. The 'truth', however, didn't make the myth of my early life any less real--any less a rooted marker of who I was and who I am or will become. And that, I owe to my mother.

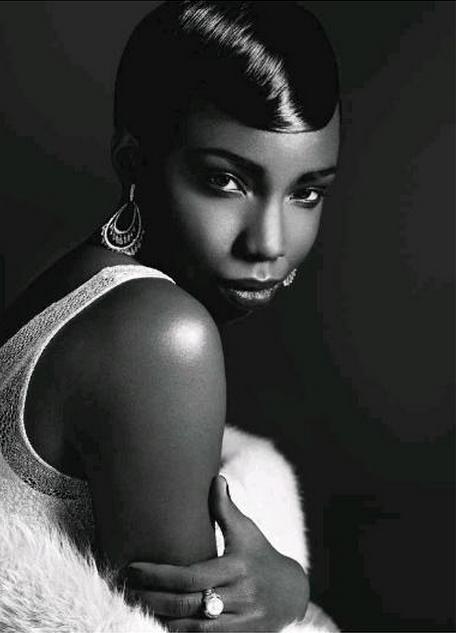

|

| Mom and I in 2009 |

You see, three years ago I was told that I was kinda, sorta adopted-- not legally with paperwork and red tape, not brought from some far off place to an entirely different family, but taken in quietly, seamlessly, secretly by the love and determination of a woman who loved my father very much. That woman became the only mother I have ever known.

My father, who I write about in "Native Speaker," has always been a very strong and visible part of my identity. The Cameroonian name I inherited from him, make my African identity proud and visible against a face that is sometimes hard to place. My Cameroonian family is large and spread all over the world and the blackness I share with them is rooted in a vibrant ancestral past and a contemporary post-colonial African present.

And yet, in key ways it was my mother who gave me kin, country and identity.

I did not have the luxury of forgetting. For in order to forget, one must first remember. Instead my early past was simply erased from my young memory by those who rewrote my history to protect, to move on, to survive. In that way my story is no different than the countless mythologies created as people leave homes and re-fashion new identities --always moving, surviving, leaving behind imprints and shadows of their private truths and hazy fictions as they go.

I am the spitting image of my mother. And yet, she was not the woman who gave birth to me.

My mother is Afro-Costa Rican. We're both "mutts", as she likes to say. Her skin looks just like mine, her first language is my first language, we were both born in Latin America. And, she too, did not grow up with her biological mother. The similarities are striking. Three years ago when I found out she wasn't my 'birth' mother, that my 'birth' mother was Indian, that after all that, I was a classic taboo--a "forbidden love child"-- it was my mother's Afro-Latina/Caribbean identity that anchored me in the face of a simple truth that threatened to uproot and displace me and all I was.

I dedicated my undergraduate life to developing my black consciousness and in particular, my Afro-Latina consciousness. I even spent a summer with my maternal grandmother in Costa Rica unearthing the lost histories of blacks in Limon, Costa Rica-- empowered by their rich transnational narratives, their liminality and their resistance as Africana people. Fluent, familiar Spanish danced effortlessly on my tongue. Rice and peas, escovitch fish and platano tasted like home. I saw my mother's face-- my face-- in everyone I saw and I felt keenly a part of a history, a people, a legacy. It was then that I realized that it was my Afro-Latina identity moreso than my Cameroonian identity that connected me to a living history of blacks in the Americas. It was my Afro-Latina identity that carved out a space for me to understand the breadth of mixedness-- of blackness, its contours, it's depth, it's beautiful distress. It rooted me to a sense of place and home that weaved me seamlessly into a diverse black Atlantic legacy charting it's way from west African shores to Jamaica to Costa Rica to my birthplace in Santo Domingo to Jamaica, Queens where I spent my early years and even Staten Island where I grew up black and middle class in an overwhelmingly white wealthy suburb-- a proud part of the multitude that contained multitudes.

Don't get me wrong, while grounding, my parent's identities did not spare me my black girl/mixed girl woes. Sure, having two black parents should have been easy enough. But from an early age I could sense that our family identity wasn't quite the 'norm.' The "mixed-up" anxiety I had and the struggles with identity I faced growing up and into my college years were a product of an alienation born from being a "hyphen"-- an "and" in a system where that hyphen is still rendered illegitimate, where multitudes are bound and limited to sound-bite definitions and caging boxes. I was a black girl in a white world. An immigrant daughter in American society. A first-generation African girl in an African-American culture. An Afro-Latina/Caribbean girl in a mestizo Latino world.

Dr. Saidiya Hartman writes "To lose your mother was to be denied your kin, country, and identity. To lose your mother was to forget your past." I lost my birth mother-- Not to death, but to the past, to culture, to tradition, to destiny.... who knows? I was denied entry to an identity, to kin and to a country that should have been my birth right.

Last year, I traveled to India for nine months to find out more about this identity, this country, this kin that was erased from my history. And as I wrote in my post "And I'm Either No One, Or I'm A Nation" India, too, felt vaguely familiar. For the first time in my life I was not automatically read as "black" and to my incredible surprise I found myself passing. That "passage" felt like an act of trespass and yet it was deeply validating. But as in most spaces, that validation gave way to the more familiar sensation that I am perpetually a stranger in a strange land. And well, that's okay. It's who I am.

Since my time in India and over the last three years I've reflected a great deal on how transgressive my racial history has been-- how constructed and (re)constructed. My experiences have shaken my previous conceptions of what race is, what family is and what identity is. They have profoundly underscored cultural critic Stuart Hall's mantra that "Identity is always in the process of being and becoming." That goes for someone with as complex a history as mine as for a whitebread kid in Ohio. The paradox of identity is that it is meant to ground and define and yet by its very nature it is always in flux. So, what do we hold on to?

For now, I hold on to my mother. The woman who gave me everything. I hold on with the understanding that this is not who I will always be, but that at the core of my mixed journey is knowing that while we may not always be writers of our past, we are creators of our future. That identities come from somewhere and have histories, but they also have transgressive and yet unwritten futures. I stand proudly in all my truths and contradictions.